The final post of Left Open, CLT’s leftist coverage of the 2023 Australian Open.

When I was in the fifth grade, my mother did some babysitting for the people who ran our local Lawn and Tennis Club. My family didn’t come from Lawn and Tennis money but thanks to my mother’s excellent childcare services, we were given two years of membership. It was paradise (read: there was a pool.) I started playing tennis when I was around ten or eleven for one simple reason: the surface area of a tennis racket was much larger than that of a softball bat. After two seasons of recreational softball, I had yet to hit the ball a single time. Not in a game, not in practice. Never. My parents became concerned about my hand-eye coordination, even though I was also a proficient violinist at the time. The pediatrician, to their relief and embarrassment, diagnosed me with sucking at softball and said I should try another sport. Hence, my tennis career began with pity.

Tennis is a rich kid’s sport. Everyone is familiar with the high barrier to entry and the obnoxious country club culture most recently popularized in the film King Richard: little nouveau riche be-skirted white girls with high pigtails whacking balls with expensive equipment in exclusive enclaves with an air of elitism that rivals perhaps only golf or equestrianism. A child understands when a place is not for them. I knew the Lawn and Tennis Club was absolutely not for kids like me - kids who got their tennis rackets from the Walmart sports department. I really, viscerally didn’t want to play tennis because I saw the kinds of people who did.

Fortunately for me, playing tennis was not a choice. Included in our deluxe membership were weekly hour long tennis lessons with a Real Coach from Europe™. We would never otherwise be able to afford such an opportunity as the lessons began at $100 an hour. My parents had long been convinced of the value in sport for children like me (antisocial, awkward, and full of anger and energy) and hoped that even the most untalented youth could eventually be coached into mediocrity given the right teacher. Considering the high price of our free lessons, they urgently saw tennis as the only opportunity for me to ever become athletically competent. Hence, one Wednesday after school, I was carted off to play tennis. My mother pulled up to the 70s mansard porte cochere, and in the backseat I felt sick with dread. In the clubhouse, I changed into my wrinkled Soffe shorts, a random t-shirt, and beat up Reeboks, and entered the tennis office just as children with perfect Nike tennis outfits and expensive jewelry to match exited, giggling and whispering. I looked at my shoes wanting nothing more to be anywhere other than where I was standing.

A gentleman in his fifties came in from outside. He had a crop of gray hair and tan, leathery skin. He paired a white polo with a gold chain. The man took one look at me and smiled - with his gold tooth.

“My name is Bob,” he said in a thick Eastern European accent, and then immediately asked, “Do you know what a palindrome is?”

Caught off guard, I replied that I did.

“Bob is a palindrome. It is spelled the same backwards and forwards. It is a special name!” He laughed a big laugh. Bob (I never learned his last name) was from “Czechoslovakia” - a great country, he reminded me often, that did not exist anymore. He was a total character. Bob had a penchant for those copper bracelets that supposedly relieved arthritis. He drank only Smart Water. He inserted pauses into the parts of sentences where they didn’t need to be. I found Bob to be very, very weird. And Bob looked at me and knew that I was very, very weird, too. He immediately clocked my insecurity in our very first lesson. “You don’t look like you want to be here,” he said, gathering a basket of balls.

“I’m not good at sports,” I said.

“You have never played tennis. You cannot be bad at something you have never done.” We hit some balls. I sucked, but Bob pretended not to see that. He told me about Czechoslovakia and how they had the greatest sporting program ever and that everyone played sports even if you were poor. My parents were not poor but we were not rich either - I said that I wouldn’t be here if my mom didn’t babysit for the owners.

“So what?” Bob said. “We will make you a good tennis player, but you have to want to be a good tennis player.” He gave me one of his woo woo bracelets, telling me that it would “realign my chakras.” Maybe it did.

From the very first lesson, I really liked Bob. He was a total crank in some respects, a mystic in others, and quite frankly, a kooky old man in others still. But he coached me into being a decent tennis player. He could see that I had a mean serve but lacked agility in the backhand. I could run fast but was prone to tripping. I suffered from insecurity which amplified all these other problems. He targeted that the most. I listened to Bob simply because he was also an outsider, but despite that, he became good at sports at the same time. We did yoga after every cool-down, right there on the court. He used to hum Bach when he hit balls to me and only ever addressed me as “Ms. Wagner.”

These tennis lessons were a minor episode in my childhood, and I’d even forgotten them for some time, until I started watching tennis again a year ago. Many of the same players I remembered from childhood were still around - Federer, Nadal, the Williams sisters, but their careers were waning. I had to pick someone new to root for. I picked Novak Djoković for one reason: he reminded me a lot of Bob.

Djoković is a divisive athlete. When I watch him on the court, the fluidity of his play and the sharpness of his intellect astound me. He is a beautiful tennis player, adroit, clinical, brutal. Sometimes I feel as though he sees what is going to happen before it happens - even before the ball hits the surface of his opponents’ racket, he knows its trajectory, his body is already moving, he is looking up, already waiting for the parry to a shot he hasn’t yet taken. I would give anything to know what it feels like to be able to play a sport with that kind of supernatural competence, with that satisfying ruthlessness. I also get the sense from Djoković that he is motivated by an undefined and indefatigable anger and pride. This is perhaps unattractive, but nonetheless, we share this in common.

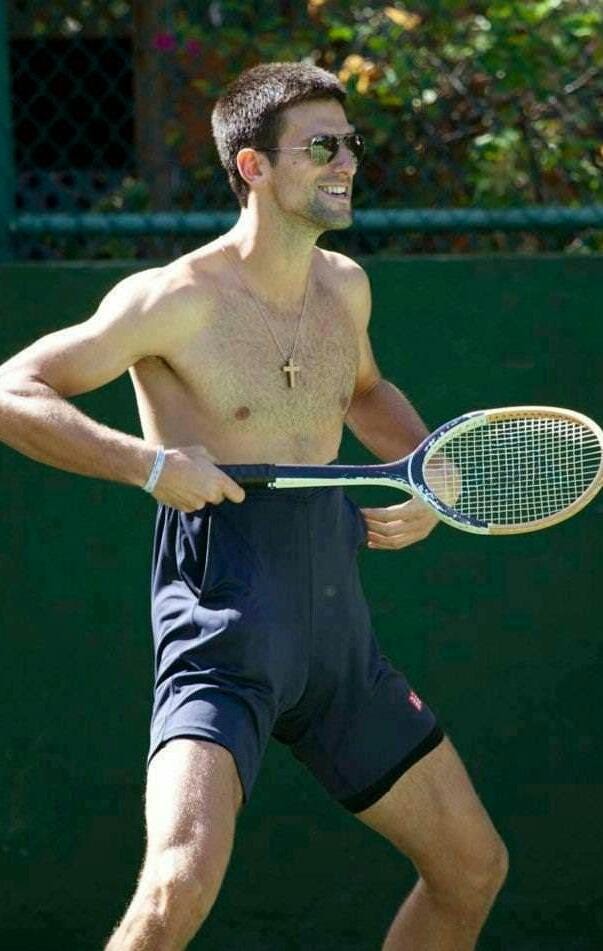

And yet, for all his tennis prowess and success, as a person, Djoković is extremely offputting. He is, in many ways, a crank and a contrarian. Take for example, the whole long, embarrassing saga in which he refused the COVID-19 vaccine. (The saga seemed to me to be increasingly concerned not with the vaccine itself but more with Djoković not wanting to be told what to do by anyone, ever.) Reportedly, the Serbian ace believes that water can be purified with emotions and that his visits to the Bosnian pyramids in Visoko will charge his body with positive ions - whatever that means. We are not talking about highly coordinated run-of-the-mill libertarian crankism bankrolled by millions in dark money, but rather a collection of esoteric ideas that make such little sense to a rational person, they blur the line between legitimately harmful and obtusely farcical. Beyond his selective homeopathy and preoccupation with the paranormal, Djoković’s more inoffensive behavior is also unsettling. There are countless videos of him dancing to “Gangnam Style” in the year of our Lord 2022. He compared winning the US Open to sex. Then there’s whatever’s going on in this picture. Indeed, on the court, Djoković is one of the best athletes alive. Off the court, he is best described as some kind of tennis cryptid.

One thing I’ve learned in my brief time in sports journalism is that crankism is rampant in sports to an extent civilians wouldn’t otherwise expect. Athletes are like artists - ineffably talented and as a result, their view of the world is a little off. Covering professional cycling, I’ve heard everything from anti-vaccine rhetoric to the idea that lasers cure back pain, to the myth that cyclists should never under any circumstances walk up stairs because even one story would fuck up the mojo in their legs. Djoković may be one of the most visible cranks in sports but he is not very unique. He is, however, special when it comes to his other forms of weirdness. While I don’t deny the impact of his vaccine denialism, (I believe in science and think everyone should go out and get their COVID booster), Djoković’s more harmless idiosyncrasies I deeply respect. I love the shorts picture. I love his stupid dances and memeable faces. I love his odd, inexplicable friendship with Nick Kyrgios - another abrasive weirdo infamous for his emotional outpourings and a penchant for wearing basketball jerseys. I love Djoković’s trolling of the press, which even as a member of the press, I can admit we deserve sometimes. I love that Djoković is a freak because sports should be for freaks, too. You don’t get to deny someone access to sports just because they’re a little off. The idea that an athlete is some kind of ubermensch who represents the ultimate achievement of what humankind is capable of is a prison in its own right for both athletes and fans. Holding up sportspeople as untouchable heroes is childish behavior that will only lead to profound disappointment. In this respect, Djoković is doing us all a favor by bursting that bubble over and over and over again. He forces us to have to live with the complexity that talented people can also be strange, that bodily perfection and moral or behavioral perfection do not inherently coexist, especially in a sport like tennis which favors propriety and good behavior above all.

Ultimately, many people including myself perhaps envy Djoković simply because the concept of cringe is foreign to him. For better or for worse, he is liberated from cringe. I sincerely believe that this gives him a competitive edge, just as it gave Bob his competitive edge when he played tennis somewhere in Czechoslovakia. When I was taking tennis lessons, the concept of cringe did not exist in its contemporary form, but it was what Bob spent most of his time trying to eradicate in me, his pupil. My biggest holdup in tennis wasn’t that I was bad at sports but that I feared being bad at sports - I lived in terror of embarrassment and humiliation. Bob’s solution to that was to inoculate me against that embarrassment - by doing yoga, wearing chakra bracelets, talking about palindromes, humming inappropriately. The more I was allowed to live with embarrassment, the better tennis player I became. Hence, every time I’m sent an update on the various ridiculous antics of professional sportsman Novak Djoković, I laugh, sure. But deep down, I know that it is Djoković who, in his incomprehensible freedom from shame, is probably laughing right back at us.

Kate Wagner is a cultural writer and sports journalist

A very enjoyable read, this is.

At fist, seeing the photo and not even looking at the byline, I thought it was Djoker's own story, at least until the paragraph with the comparison to him.

However, also up until that point I kept thinking how well written this was and that if coming from the arguable GOAT, he most certainly had a ghostwriter!

My point is that I wish to see more tennis stuff from this Kate Wagner!